What Can Fields Like Epidemiology Teach Us About Building Ethical Social Applications?

Article by Nick Walsh — Nov 20, 2020

What does going viral mean to you? Popularity? Successful promotion of some piece of content? To epidemiologists — or, really, just about any human person in the midst of this pandemic — virality doesn’t come with cheery overtones.

In the context of a social platform, what if that “success” spreads disinformation? What if reach leads to abuse for the author? Adding community-driven features can make for a compelling product, no doubt, but ethical tech companies have a responsibility to the users of that product. Sadly, (and more on this in a minute) disinformation and abuse aren’t hypotheticals. They’re the everyday reality for much of our online social infrastructure.

Many of the articles we write guest star the same trend: Web applications have become more and more complex over the last few decades. The industry has adapted through a pair of paths:

- Deeper specialization. Titles like UX designer, front-end engineer, and devops engineer have been added to an ever-growing team.

- Turning to established research and fields. Fundamentals like animation principles, accessibility studies, and data visualization standards were catalogued long before the web had the capability or need for them.

As we look at the unwritten ethical contract between social software and the people that use it, there’s still a minefield of knowledge gaps. Do developers have a handle on the sociology behind users grouping together? Does the UX team know when it’s appropriate to make something harder to do? Are there parallels in a field like epidemiology and the spread of lies?

Before we start brainstorming, let’s cover the reasons driving the need.

Missing the Humane in Humane Tech

Thanks to research, government reports, documentaries, and awareness of the extreme divisiveness that surrounds us, we’re slowly seeing the edges of our social bubbles. For a lengthier introduction, check out the recording of my Digital Orlando talk.

Revelations in hand, the industry has realized that:

- In a social setting, tolerance doesn’t mean tolerating intolerance.

- Addiction, misinformation, and abuse that occur on community platforms aren’t just a personal problem for the user.

- Despite a lack of regulation, at a minimum, the service must share in the responsibility of being an ethical steward of information.

With that mandate, how can technologists tackle social features in a meaningful way?

Social Application Features, Drawn From Other Fields

Sometimes, the best bits of creativity come from flipping the process on its head. Instead of starting with a feature or objective, we’ll look to related fields and find overlaps to explore.

Epidemiology and Disease Control

As mentioned up at the start of the article, the spread of information isn’t always a net positive. Falsehoods and harm shouldn’t have reach. When they do, content starts to look more and more like a contagion (the term or the film). Analogy settled, we’ll walk the path of disease control first:

- Quarantine. Generating a fake bit of content for the first time probably isn’t worthy of a ban. A sufficient warning, though, could include a quarantine-like moratorium on posting for a user — one that increases in length with each subsequent offense.

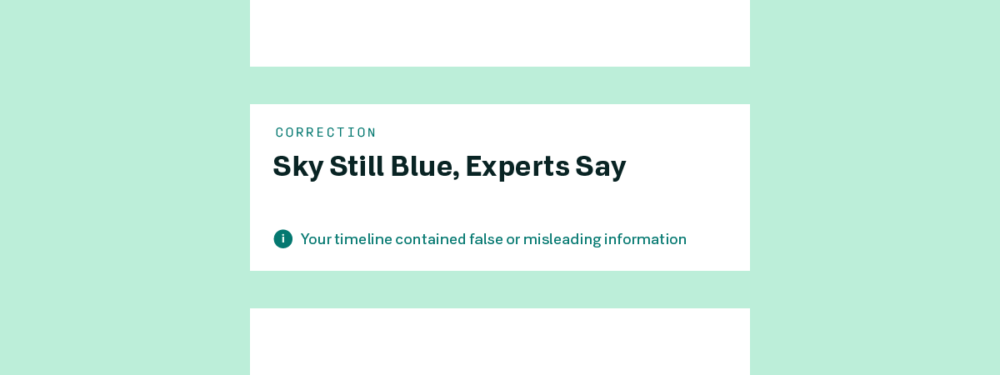

- Contact tracing. As misinformation is identified, the platform can sort out who saw it and counter with the truth. A single correction may not be enough to change someone’s mind, but research points to multiple reminders moving the needle.

- Vaccination. Harking back to our assertion that tolerance doesn’t include supporting intolerance, there are topics that don’t deserve the chance to spread. Bans — like the ones introduced on Facebook and Twitter this month for Holocaust denial content — aren’t a silver bullet, but they move an ecosystem closer to herd immunity.

Psychology

In Daniel Kahneman’s Thinking, Fast and Slow, our two modes of thought (System 1 and System 2) are covered in detail. It’s well worth a read, but to summarize here: Humans use System 1 for instinctive thought and System 2 for things that require a bit more pondering. It’s akin to the difference between calculating 1+1 and 17×17.

User experience designers usually aim to make interfaces and flows that can be described with adjectives like intuitive, simple, and fast — all things that sound a lot like System 1. If it becomes intuitive to share misinformation, though, is that good UX? Let’s ideate around features that slow things down:

- Add friction. I prefer to separate when I read from when I reply to emails. Adding that extra step (and a bit of a gap) removes a lot of emotion from a medium that doesn’t communicate it well. A similar cooldown could be codified into online replies, especially for divisive topics, to tip thinking towards System 2.

- Read first. Judging a story by its headline is a huge issue when it comes to sharing misinformation. How about displaying a helpful reminder to read the story first, to give users a chance to ponder their choice? Twitter’s already seeing positive results with their take.

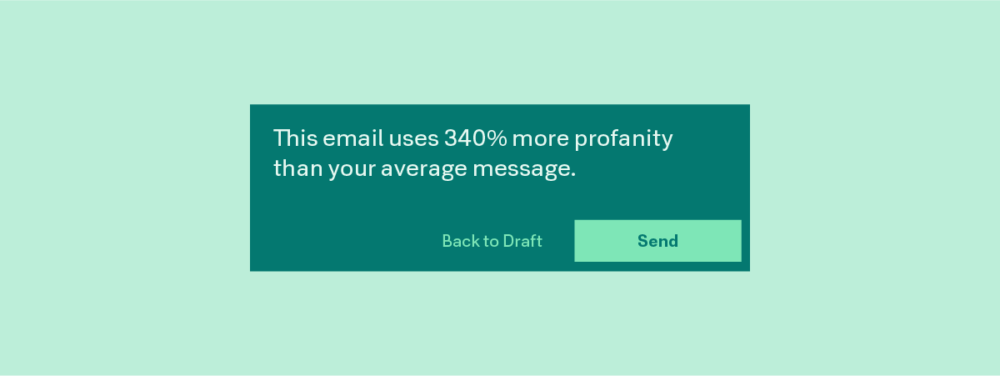

- Check intent. Email clients can already detect if we meant to attach something and forgot. What if they scanned word choice and tone to provide feedback before we fire off an angry message? Amazon’s new fitness bands have a similar feature; if it’s successful, expect mindfulness apps everywhere to follow suit.

Sociology and Data Science

The bulk of the web’s discourse used to happen in anonymity. Blog comments, message boards, forums; what you said wasn’t linked to who you were. As discussions moved to platforms with the opposite aim, it was widely assumed that decorum would follow. It stands to reason — if your family, employer, and friends can all see what you write, societal norms will take care of moderation, right?

Data, of course, points to no. Just look at the replies of any prominent politician on Twitter, or the puzzling use of LinkedIn as a dating site for so many.

A key accelerant has been the formation of those algorithmic social bubbles we mentioned earlier. In a bid to recommend content that holds our attention, social platforms have optimized around showing us people and posts that match our worldview. This creates a closed loop of reinforcement that amplifies confirmation bias and anger.

We’ll look at group dynamics and bubble popping for the next set of feature explorations:

- Fairness doctrine. Prior to its repeal, the FCC’s fairness doctrine dictated that broadcasters present controversial issues in an honest and balanced manner. What if social feeds had a similar mandate, so long as the opposing view wasn’t misinformation or intolerant?

- A peek at the stats. From within a tailored list of content, it’s tough to recognize that ads and promotions are targeting you for a reason. Seeing the breakdown of why a particular item has been brought to your attention (demographics, interests, history) could help identify intent.

- Review repetition. At its most extreme, social media has been used to incite military-sponsored genocide. Where there’s repetition of hate and misinformation within a group or network, what if the ideas around quarantine (temporary bans) and contact tracing (multiple imprints of the correction) from earlier were applied at the community level?

Further Resources for Inspiring Ethics

We’ve only skimmed the surface on paths for features that give software an ethical lean. Data science, diversity and inclusion, anthropology: There are many more fields with insights that can be applied.

With the release of a tech product into the world, companies take on a series of new responsibilities. Numerous as those responsibilities are, adding community-driven features introduces a whole lot more. The effect of ethics taking a backseat to attention and growth has been painful to watch, but the power to affect change currently sits with the people building the platforms.

For further reading, check out:

- Jon Yablonski’s Humane by Design, a (beautiful) resource for humane patterns and approaches to experience.

- Ofcom’s report on AI in online content moderation.

- Google’s guide to machine learning for marketers, which talks about algorithm bias and how it really impacts users.

Up Next —

CRDTs: Eliminating the Central Server in Collaborative Editing

The difficulties associated with collaborative editing have hit home during this pandemic. Find out why conflict free replicated data types could be the answer.

Read this Article →